In his 1964 book on Protestant architecture the pioneering worship reformer historian, James F. White, lamented that at that time there were essentially only two types of worship space in America. One was what I have called the classic auditorium, the other is what we will call the divided chancel. The Cathedral Church of the Advent exemplifies this type. (White 1964).

Altar as centering focus

Unlike the auditoriums, the focus here is not on worship leaders, but on the altar (or communion table). It is located at some distance from the congrgation at the end of a wide central aisle that is used weekly for processions.

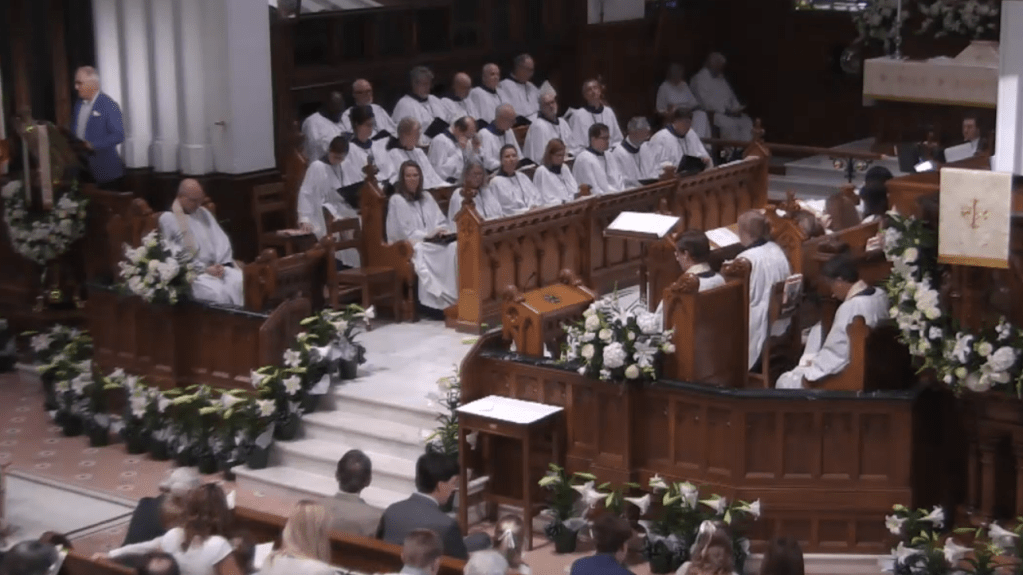

The choir does not face the congregation, but is arranged facing each other across a central aisle between the chancel steps and the altar. The clergy also do not sit facing the congregation, but sit inline with choir, perpendicular to the congregation. This arrangement is valued for suggesting that the key action is worshiping God, or personal prayer to God, not listening to a person. It seeks to emphasize that the church is in part a temple and not just a meetinghouse. The altar provides a devotional focal point to which worshipers can bring various meanings.

Many Spaces for Worship Leaders

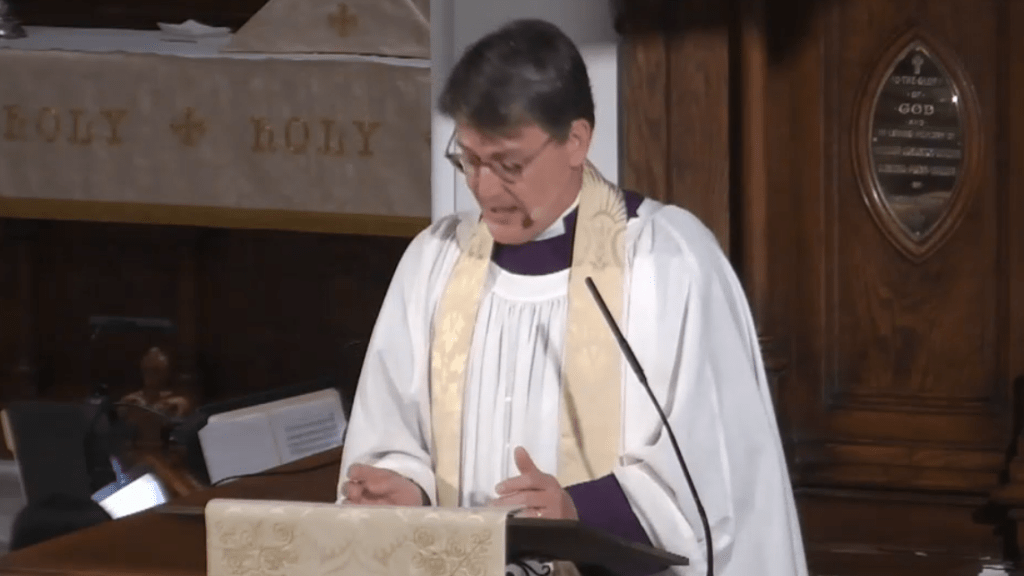

While in an auditorium church the clergy lead the entire service from one place: the central lectern (usually called a pulpit). Here, there are at least three places where leaders commonly lead the word-focused portion of services: the lectern (which is often, as here, shaped like an eagle), their seat (or stall) where they can both stand to speak to the congregation or kneel to lead them in prayer, and the pulpit, located on the opposite side of the chancel from the lectern. Additionally, these days, clergy often speak to the congregation from the middle of the chancel steps, or walk down to the congregation’s level. Lastly, the celebration of holy communion, and sometimes the offering of some other prayers, takes place at the altar at the far end of the chancel. And very importantly, the laity complete their own procession into the church by walking all the way up to kneel at the high altar to receive communion.

Images above are screenshots of March 31 and May 19, 2024 services streamed on Facebook.

All of these different places enable different meanings to be invested in an action depending on where it occurs. To speak from the pulpit is often seen as speaking with great authority, whereas readings from the lectern might be seen as having lesser authority. Speaking from the top of the chancel steps facing the congregation is often seen as more informal than speaking from the pulpit, lectern, or clergy stalls. Thus, in many churches like this, this open area is where announcements are given, less formal sermons, and where children sometimes assemble for a children’s message. When the bishop visits, it is also where her chair is placed and where she presides. It is this chair (Latin cathedra) that makes the church a cathedral.

One challenge in a divided chancel church is where to baptize. A traditional location for the baptismal font is at the west end of the church, near the entrance. This is to symbolize that one enters the church through baptism. This is where it is located at the Cathedral of St. Paul. At the Advent is also at the west end, but in a vestibule that cannot be seen from the nave. This works fine for small baptismal services with just the family as were the norm when the font was placed there. Now, however, this church often baptizes in the main service. On these occasions a small basin is placed on a table at the foot of the chancel steps. (Sprinking or pouring is the normal form of baptism in this church.)

The Position of the Altar

The position of the altar is also very important and often debated. At the Advent, the altar was originally against the wall. It has been brought out from the wall a couple feet, so that the priest no longer faces the same direction as the congregation in the nave (and thus has his back to the people) instead he faces the people across the altar. This change was made among many denominations in the 1960s and thereafter in order to emphasize that the eucharist was a communal action in which all participated in the prayers. Others, however, suggest it makes it even more of a performance by the clergy. Thus the symbolic resonance of both positions is debated. One of the few local churches that where the priest still celebrates facing the same direction as the people (known as ad orientum) is St. Mary’s-on-the-Highlands Episcopal Church, though this may be more due to the tight spatial constraints of its sanctuary than to anything else.

In many large churches with a divided chancel the altar has been brought forward to in front of the pulpit and lectern so that it is closer to the people. Here at the Advent, however, it remains near its original position. As we will see in our look at Yeilding Chapel, some churches have been built to place the altar completely in the middle of the people.

Stained Glass

The symbolic resonance and aesthetic impact of the Advent is strongly shaped by its rich collection of stained glass windows. The windows were added overtime from the 1890s to the 1950s and represent all the various styles of stained glass popular over that period. Many of its windows render painting-like scenes similar to those at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church or the Cathedral of St. Paul. Others, however, are mosaic windows that are more similar to medieval windows and present a variety of small scenes and symbols using many small pieces of glass. These windows first goal is to contribute to the overall lighting and aesthetics of the church. Their detail repays careful study, but often cannot be worked out while sitting in the pew. They do not seek to distract from the overall worship environment.

Despite James White’s 1964 claim that the classic auditorium church and the divided chancel were the only options American Protestant were using, there was at least one example in Birmingham that sought to offer the best of both options, and it would soon be joined by others as we’ll see in the next essay.

In addition to the choir-led worship services depicted above, the Advent also offers band-led worship that employ a different musical style. Currently this are held in another room, but in 2021 they were held in the cathedral itself. This previously-written student essay describes that service:

This page is part of “Spaces for Worship: A Birmingham-Based Introduction,” a section of Magic City Religion, written by the editor and funded by Samford University’s Center for Worship and the Arts.