While many are attracted by the altar focus provided by the divided chancel, some choir directors were not. In 1949, when the leaders of Highlands United Methodist Church proposed remodling their church from a classic auditorium to a divided chancel, the choir director objected and said he would not direct a divided choir. He lost the argument and resigned his position (Fort 1987). Independent Presbyterian Church (IPC) which opened over twenty years earlier embraced a middle path.

Here the choir sits facing the congregation in a loft. But this loft is placed above the pulpit and altar and has a somewhat high front parapet. Thus when the choir is seated, they are not that visible to the congregation on the floor. As in a divided chancel, the altar (or communion table) is central and it is embelished and ritualized with a cross and candle sticks. A tall tub pulpit is provided for the sermon and a separate lectern for the readings. (Both have green hangings on them in the above photograph. The baptismal font is located to the far right, under the edge of the balcony so that baptisms may easily take place during the worship service.

The arrangement at IPC has brings the communion table close to the people. The clergy sit right behind it in seats built into the base of the choir loft. But since the floor is not sloped and its position not greatly elevated, it is difficult for some in the church to clearly see the altar.

Worshipers experience of this church is more static than services at the Advent. Communion is typically served to them in their pews, there is no chancel for them to go up into. Also the church is shorter. The focus of the church, whether understood as the altar, or the window of Christ’s second coming above the choir, is nearer to the congregation.

With its heigth, gothic detail, and excellent mosaic glass windows, IPC is Birmingham’s best representatives of the many commanding buildings in Gothic and other historic medieval styles designed in America from the early twentieth-century into the 1930s. The most effective promoter of such buildings was architect Ralph Adams Cram who not only designed buildings, but wrote about them especially in his very influential Church Building (first edition 1901). His views were also echoed by influential clergymen such as Von Ogden Vogt and Elbert M. Conover. Indeed IPC, designed by the Birmingham-based firm of Warren, Knight, and Davis, derives its plan and many of its features from First Baptist Church of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which was designed by Cram’s firm, specifically his partner Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue. Like First Baptist, IPC was “combination church” with a moveable partition wall separating the sanctuary from the auxillary room on the side (now the church parlor).

These medieval inspired buildings sought not only to be artisticly inspiring places, but also to be explicity a “House of God” with a clear devotional focus on the altar. Balencing this Protestant sensibilities that emphasized the church a meetinghouse and highlighted communal action was sometimes difficult.

Another church in Birmingham that takes a very similar approach to IPC through in a modernist architectural style is Vestavia Methodist Church. In the photograph below, the baptismal font is located in the middle of the central aisle in the midst of the congregation.

In renovations, other churches, such as All Saints’ Episcopal and South Highland Presbyterian Church placed the choir behind the communion table of a divided chancel, but not highly elevated as at IPC and Vestavia Hills Methodist.

As churches have been willing to embrace asymetirical solutions to their liturgical plans, other possibilities opened. This enabled Trinity United Methodist Church to place the choir in a very traditional chorus arrangement to the side while still having the altar alone as the terminus of the church’s main processional aisle.

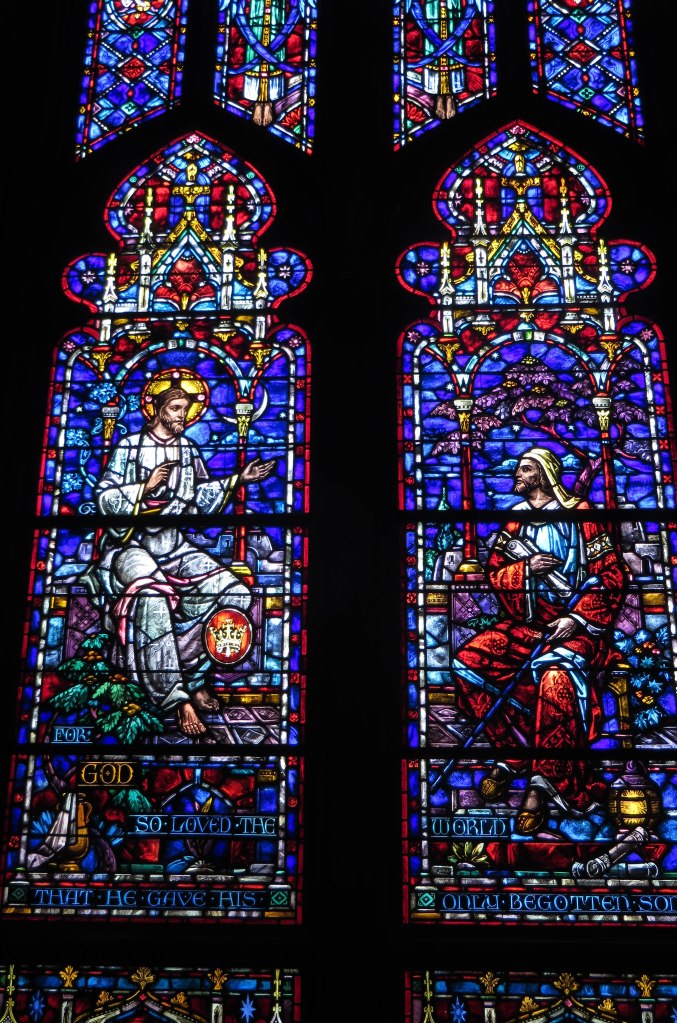

The stained glass windows at IPC and Trinity both employ small peices of glass in the mosaic Gothic style, but use them to create large scenes that are fairly easily read by worshipers in the pews. Unlike the painterly windows at Sixteenth Street Baptist, however, they are not directly based on paintings and are arguably more authentic to the medium of stained glass: They carefuly modulate the light entering the nave and appear flat, rather than suggesting a depth of field.

To explore our next variety which employs a different solution to the altar-focused church, click here.

This page is part of “Spaces for Worship: A Birmingham-Based Introduction,” a section of Magic City Religion, written by the editor and funded by Samford University’s Center for Worship and the Arts.