Hodges Chapel at Beeson Divinity School on the campus of Samfod University is one of the few Birmingham churches with a true pulpit as the centering focus of the church. By “a true pulpit,” I mean it is not merely a speaking desk on a platform that is shared with other chairs for worship leaders, as in classic audtiorium churches such as Sixteenth Street Baptist. Instead, it is an enclosed platform into which a speaker ascends. Behind the speaker there is no elevated choir. There is no rival sharing her central position.

The pulpit stands unrivaled as the chapel’s central focus. Standing in it, you are the center of attention of the entire church. Everyone can see you. You are elevated into an authoritative position and constrained a bit in your movement. The sides of the pulpit, and its speaker‘s desk, are relatively low. So it is not just the head and shoulders that the congregation can see, as in some central pulpit churches. But this is still a space that demarcates the centrality of the preaching and proclaimation of the word. Its spatial dynamics focus solely on proclaimation.

As seen in the first image above a communion table is usually placed below the pulpit, but it draws no attention to itself except when used, and sometimes (as in the second photo above) it is removed from view.

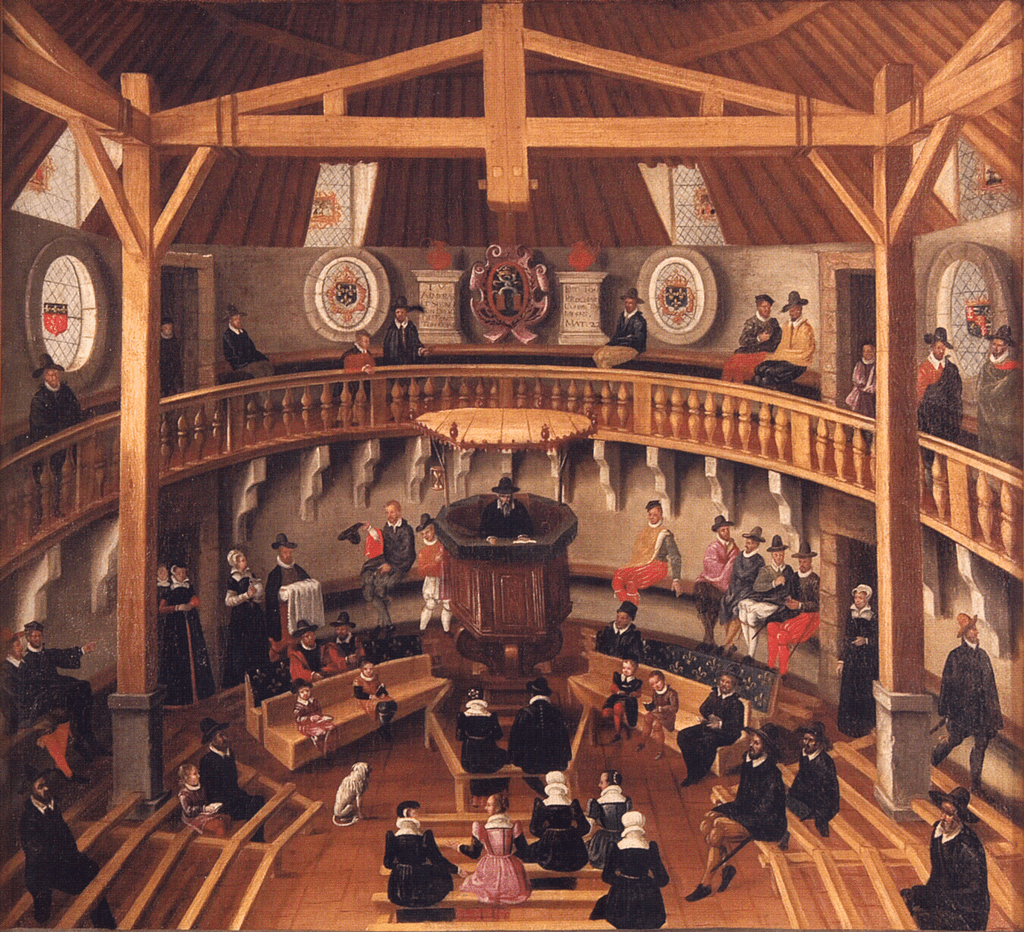

The central pulpit was a very common arrangement for Protestant churches from the 1540s to 1880s when the auditorium church replaced it. A painting of Temple Paradis in Lyon, France, is our oldest visual evidence of a church erected for worship in the Reformed (as opposed to the Lutheran or Anglican) tradition of Protestantism (1565).

While many churches in the United States were built like this, most, if not all, of the old ones in Alabama were altered to provide a platform with chairs for the various speakers rather than a high pulpit. These high pulpits worked against the personal appeal evangelical churches desired.

I know of no church in Birmingham that emphasizes the pulpit as much as Hodges Chapel, but there are a couple others have pulpits as their central focus, but in each of these other cases there are strong secondary focal spaces such as an altar, a prominent lectern, or choir space.

In Hodges there appears to have been no planned place for musicans other than the organist. A piano has long been placed on the north side of the altar and worship leaders for “contemporary worship” are frequently arranged there. At other times, a choir has been placed standing behind the pulpit. But in both of these locations, the musicans must stand they cannot be seated in these places.

When the current pulpit was installed in August 2001, a lectern was placed on the floor on the south side of the pulpit as a secondary speaking position. It is often used, but it is much, much lower than the pulpit and speakers standing there cannot be seen by many worshipers in the nave. The temptation to use it is understandable: climbing into the Hodges Chapel is daunting. The lectern is more accessible, but in my experience any actions performed there are so spatially and symbolically subordinated to what occurs in the pulpit that it does not seem like an appropriate place to read scripture or offer prayers.

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, the pulpit was often moved for the services held by other groups. These included Christ the King Anglican Church, a congregation started by Beeson Divinity School professor Lyle Dorset that met in the chapel on Sunday mornings for many years, and Shiloh, a student service that occurred on a weeknight in Hodges Chapel until it outgrew the space and moved to Reid Chapel. However, due to the inevitable wear-and-tear moving furniture entails, the movement of the pulpit is now much less common.

History and Iconography

Andrew Gerow Hodges Chapel is unique in many ways aside from its arrangement of liturgical centers, and intentionally so. In 1988 Samford University (a Baptist institution) founded Beeson Divinity School because of a gift from businessman Ralph Waldo Beeson. Beeson belonged to a Presbyterian church and his father had been a Methodist college president. Accordingly he specified that this school for preachers would be interdenominational. The school now describes its identity as “confessional, evangelical, interdenominational, and Reformational.” Beeson also specified that the school would have a signficant chapel. He died in October 1990, near the beginning of the school’s third year of operation when it was still in development, so the form of the chapel owes more to Samford leaders such as President Thomas E. Corts and Dean Timothy George, as well as their architect, Neil Davis.

In an interview a decade after the completion of the chapel, Corts explained that they desired a “very special chapel. Something that someone would drive a great distance just to see” (Theologie 2005). The chapel achieves this though a commanding dome, abundant classical detail, and extensive iconography in paint, stone, and wood.

It is very significant in the symbolic resonance it encourages through its twenty-eight images of post-New Testament Christian figures or events. Until St. Symeon Orthodox Church was erected, this was the largest collection of post-New Testament figures in a church in Birmingham. Around the base of the dome there are sixteen named figures spanning the third to twentieth centuries who represent the “Cloud of Witnesses” referenced in Hebrews 12:2. In the crossing and aisles are busts of six Christians martyred in the twentieth century. On the pulpit are preachers from four eras of the church. Martin Luther’s posting of the 95 Theses is positioned as the culmination of the church year (Reformation Day) in the north transept. The donor and his father are commemorated in a medallion at the center of the chapel.

Such evocations of the span of church history are often present in major churches, and their inclusion at Hodges Chapel explicitly seeks to raise this church to a landmark status and with it Samford University.

To learn more about the iconography of Hodges Chapel visit its website where there is a video and a digital copy of the guidebook. Students have written essays on many of the images in Hodges Chapel and their subjects. You may access them here.

This is the last of the eight representative worship spaces examined on Spaces for Worship. Click here to continue with the final section of Spaces for Worship.

This page is part of “Spaces for Worship: A Birmingham-Based Introduction,” a section of Magic City Religion, written by the editor, David R. Bains, and funded by Samford University’s Center for Worship and the Arts.