Spatial Dynamics

One of four factors shaping the experience of worship spaces.

How do people move through the space and how does it position them in relation to each other, God, and the world? In Theology in Stone, Richard Kieckhefer suggests that church buildings are designed to foster the spiritual process that their congregations recommend to their adherents. He sees three most churches as recommending one of three processes “procession and return, proclaimation and response, or gathering in community and returning to the world” (Kieckhefer 2004, 21).

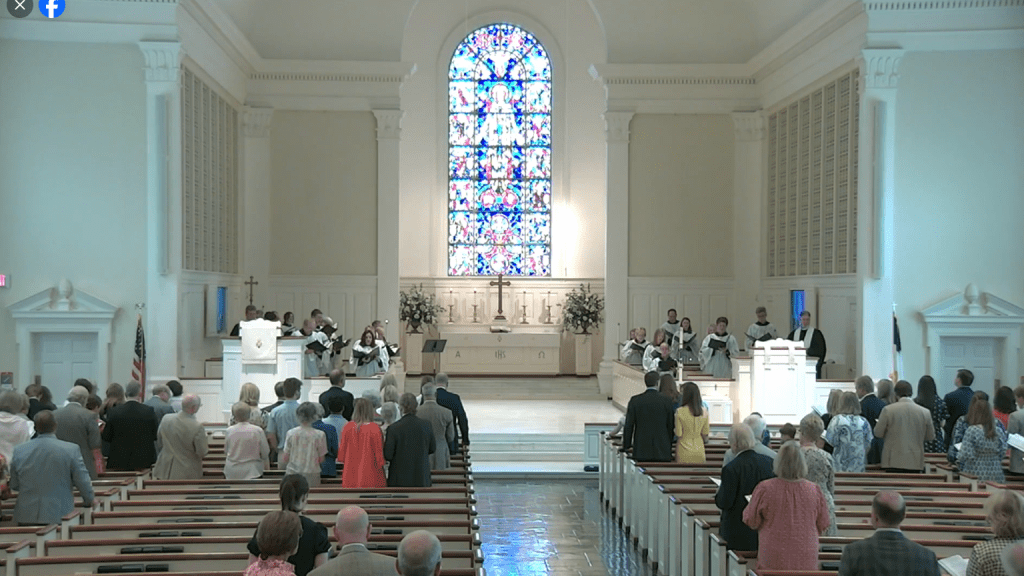

The way people move through the space and the way different spaces are used are key factors in spatial dynamics. They can give people very different experiences of similar churches. For example, the Cathedral Church of the Advent and the sanctuary of Canterbury United Methodist Church are both large divided chancel churches. At the Advent communion has traditionally been served to people kneeling at the communion rail that is right before the altar. To get there, worshipers process up the chancel steps through the choir (usually while the choir is singing) and then kneel at the altar. At Canterbury, on the other hand, communion rail is on the floor of the nave before the chancel steps. Worshipers do not process into the choir, they remain distant from the altar. Worshipers may have diverse experiences of these differences, but they do make the spatial dynamics of the spaces distinctly different.

Understanding the spatial dynamics of a worship space usually requires detailed considerable reflection, we will explore it in the discussion of each of our eight varieites of worship space.

As the pictures above show, the Advent and Canterbury have quite different architectural styles, though rather similar interior volumes. Both the style and the size of space shape the next factor of experience: aesthetic impact.

This post is part of “Spaces for Worship: A Birmingham-Based Introduction,” a section of Magic City Religion, written by David R. Bains, published in 2024, and funded by Samford University’s Center for Worship and the Arts.