This essay has been published on October 2, 2024, for my students in BREL 356: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in the United States at Samford University.

Geography and Pre-European Use

East Lake is a neighborhood in the City of Birmingham, Alabama, located in the eastern Jones Valley of Alabama’s Ridge and Valley domain. Valley Creek, a tributary of the Black Warrior River, flows through the neighborhood and is fed by a number of natural springs that rise through the valley’s limestone floor. While many no longer survive just upstream from East Lake, Roebuck Spring still flows with cool clear water, making it a good habitat for the endangered watercress darter.

[Spring, darter, darter mural, creek]

Thomas Tweed has defined religions as “organic-cultural flows” beginning with East Lake’s physical geography is an important reminder that the religious life (with its various cultural dynamics) is only possible because human’s biological (or organic) needs have been met.

East Lake is located at about 33.559 degrees latitude north and 86.726 degrees longitude west. It is about 725 feet above sea level. This means that at the summer solstice there are about 14 hours and 23 minutes of daylight, and thus about 9 hours and 37 minutes in the winter. In mid-January the average low temperature is 36 degrees Farenheit and the average high 54. In early August the average low is 72 and the average high is 90. The record high temperature is 107 degrees measured on July 29, 1930. In 2024 new record daily highs were set on June 24, 25, and 26.

The area is bounded on the south and east by the long ridge of Red Mountain, named for its iron ore. Red Gap, one of the mountain’s most significant gaps is just a mile and a half to the south. (Red Mountain runs from the northeast to southwest, but is generally spoken of as running east to west.) The section of Red Mountain north of the Red Gap boarders East Lake. It is often known as Ruffner Mountain and is now a nature preserve. To the north the land is more rugged marked by many hills and small valleys. Through one of these flows Five Mile Creek. Beyond that the land rises toward the Cumberland Plateau. For centuries it was land where the Shawnee and Muskogee hunted and sometimes dwelled.

Cession to the United States and Settlement (1814-1830)

The area that would be named East Lake in the late 1880s was part of the nearly twenty-tow million acres the Muskogee (Creek) Nation ceded to the United States in 1814 in the Treaty of Fort Jackson after the Battle of Horseshoe Bend or Tohopeka. Soon English-speakers of European descent and the Africans they enslaved migrated into the area from South Carolina and Georgia. They first settled in East Lake the around 1818. Motivated by what historian Joel Martin has called “the gaze of development,” they came to stay and engaged primarily in hunting and farming (Martin 1991).

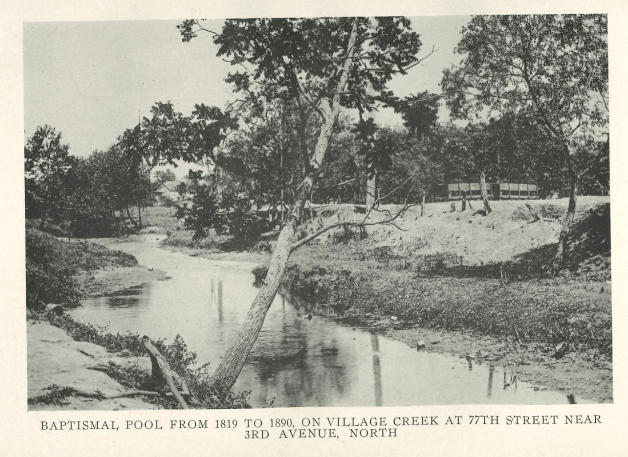

In March 1819, Hosea Holcombe (1780-1841) a Baptist preacher arrived from South Carolina. He founded Ruhama Baptist Church, the fourth church to be organized in what is now Jefferson County. Baptisms were conducted in Valley Creek. Two of the others were over seventeen miles down the valley to the west. The other was in the Pinson area about ten miles to the northeast. The area was sparsely populated with less than 7,000 residents at the time of the 1890 census.

Agricultural American Ruhama (1830-1864)

A second church emerged near Ruhama in 1834 when some members withdrew to form their own Primitive Baptist church. Primitive Baptists believed the Bible prescribed strict congregationalism that did not allow for Baptist to associate in mission societies. They also emphasized the doctrine of predestination more strongly than did missionary Baptists. But within six years, the Primitive Baptist congregation had collapsed. With few exceptions all future Baptists in East Lake were missionary Baptists. The more lasting division among East Lake’s Baptists would be between Whites and Blacks.

The valley around Ruhama remained quiet before and through the Civil War. The population of Jefferson County did not even double between 1830 and 1870 (when it was 12,345). By contrast, Montgomery County in the fertile Black Belt of the coastal plain grew three-and-a-half times over the same period to 43,704. The soil was not overly fertile and since there were not large waterways there was no way to move goods to market. While University of Alabama professor L. C. Garland spoke at Ruhama in the summer of 1854 raising capital to build a railroad through Jones Valley, no railroad entered the valley until after the Civil War.

The second building of Ruhama Baptist Church, erected perhaps 1858. Samford University Digital Collections.

As part of the Alabama Baptist State Convention, Ruhama supported the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention and the right of Christians to enslave other humans. It also opened its membership to these enslaved persons. In 1858, twenty-one enslaved persons were members of Ruhama Baptist Church. They, however, had to sit separately from the rest of the congregation and could not serve as officers of the church (Bee and Allen 1969).

Emancipation, Reconstruction, and the Birth of Birmingham (1865-1885)

It was the emancipation of the enslaved that would lead to the area’s second oldest surviving congregation. The area’s largest landowner and enslaver was Obidiah Washington Wood. His home was about three miles from the church in what would become Woodlawn. After the Civil War, Wood gave small parcels in the hills to the north of Ruhama to the people he had formerly enslaved. This neighborhood became known as Zion City. In 1869 approximately thirty-two members of Ruhama were dismissed to form Mt. Zion Negro Baptist Church. Today it is known as Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church of Zion City. Henry Wood served twelve years as the church’s first pastor. Jackson Street Baptist Church in South Woodlawn also traces its history to 1869 dismissals from Ruhama.

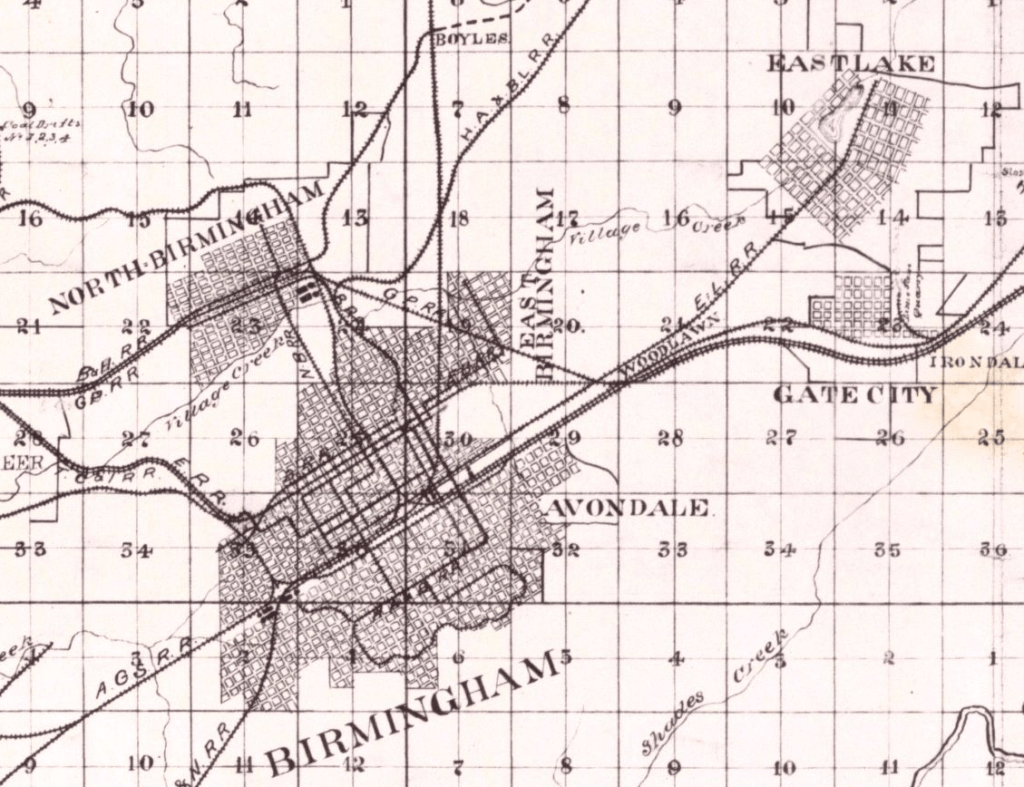

Iron production emerged as a significant industry further west in Jones Valley and the neighboring Shades Valley during the Civil War. In 1871, the City of Birmingham was founded five and a half miles down the valley (to the west) from Ruhama, near where two railroads would soon intersect. One of them, the Alabama & Chattanooga, crossed into Jones Valley through Red Gap near East Lake. Birmingham soon grew like “magic” due to the combination of good transportation, limestone to be quarried, iron to be mined in Red Mountain, and coal to be mined from the hills north of the valley: everything necessary to make and ship iron.

Birmingham’s magical birth increased Jefferson County’s ethnic and religious diversity. The county’s first Catholic church, St. Paul,was established in Birmingham in 1872. The area around Ruhama, however, remained quiet. Neither railroad passed through it, so it was not immediately transformed by the boom.

The Birth of East Lake (1886-1920)

The development of the Ruhama neighborhood into East Lake began in July 1886, when developers James Van Hoose; Robert Jemison, Sr.; and Rufus Hagood formed the East Lake Land Company. They dammed Village Creek just west of its confluence with the stream from Roebuck Spring to create a forty-five-acre lake. Around the lake, the planned a large community. The following year, they opened the East Lake Railroad, a trolley line, to bring people the five-and-a-half miles from Birmingham to the area surrounding the lake.

By promising a healthful, quiet mountain lake village near a burgeoning center of population the developers persuaded Alabama Baptists to move their liberal arts college for men, Howard College, to East Lake. For the previous seventy-five years it had been located in Marion, a Black Belt county seat seventy miles to the southwest. After moving, college leaders and students found the situation in East Lake to be far more rustic than expected. Only the central unit of a large college building was erected. But later it was joined by other buildings around a shady lawn. Howard College remained in East Lake for seventy years.

for the proposed campus of Howard College in East Lake

Whereas Marion was established as an enslaving community, in which Whites and enslaved Blacks lived and worked in close proximity, East Lake developed as a segregated community in which Whites enforced stricter segregation between the races in order to maintain their supremacy over other citizens. The oldest African American community nearby was the aforementioned Zion City where First Baptist Church of Zion City joined the previously existing Mt. Zion Baptist Church in 1911. (It is not unusual for the second Baptist church in a community to claim the name “First Baptist” if the older congregation does not use it.) Additionally, up the slope of Ruffner Mountain to the south the Brown Springs community developed. Its oldest church is St. James Baptist Church organized in 1890, just as East Lake was beginning to develop. The African Methodist Episcopal Church organized its congregation, St. James, eighteen years later.

Along the trolley line on the valley floor, the Southern Baptists at Ruhama were joined by other White denominations. East Lake Methodist Episcopal Church, South was founded in 1887. Southern Presbyterians followed in 1891 and Cumberland Presbyterians in 1894. In 1908 they were joined by Roman Catholics.

While East Lake was never an industrial center, it was not far from the mines at Ruffner Mountain and the rolling mill in Gate City. The rolling mill in Gate City attracted Belgian and Irish immigrants and they erected Holy Rosary Roman Catholic Church in 1889 so that priests could celebrate mass in their community. It is the oldest wooden church in Birmingham still in regular use by its original denomination.

East Lake itself prospered as a retreat from the city. The park boasted a rollercoaster which remained a popular attraction through the 1920s. These entertainments were for Whites only.

Suburb Achieved (1920-1950)

By the 1920s, East Lake was an established suburban neighborhood linked to Birmingham by streetcar lines and the growing use of automobiles. In 1925 the Methodist church completed a large new Christian education building on its land, just across the street from Howard College. The next year Ruhama Baptist Church opened its new classical revival building just a couple of blocks up the street. Soon Wesleyan Methodists, the Christian Missionary & Alliance, the Episcopal Church, and the Church of Christ all had congregations in East Lake.

The era was also marked by growing diversity and resistance to it. Italian immigrants began cultivating the land between Zion City and East Lake for truck farming (i.e., vegetable nearby markets) in the early twentieth century. St. John the Baptist Catholic Church was established to serve them in 1923. The land they cultivated eventually became part of the Birmingham airport.

In the same year the branch of the Klu Klux Klan located in Wahouma (the neighborhood between Woodlawn and East Lake) held an induction ceremony for 2,100 new members in East Lake Park.

The favored economic position of East Lake by the mid 1920s is well represented in Birmingham’s 1926 zoning map. On this map the residental neighborhoods believed to be more economically stable are colored in yellow and the less stable ones in pink. African American neighborhoods are marked with diagonal dashes (blue areas are commercial). Thus it can be seen that the only African American neighborhood within the City of Birmingham near East Lake was Brown Springs (in the bottom center). (Zion City was outside the city limits, off the map to the north). Nearly all the rest of the neighborhood is regarded as being of the best quality.

Since it was a favored neighborhood, White Catholics, Presbyterians, and members of the Church of Christ all erected significant buildings in East Lake in the mid-century. Methodists and Presbyterians joined their central churches with smaller nearby neighborhood churches. After World War II, a few other denominations organized in the neighborhood including Lutherans, Pentecostal Holiness, and Disciples of Christ, and the Church of God (Anderson, IN).

[Pics to come]

1950s and 1960s: A New Era Slowly Begins

Post World War II government policies (the G. I. Bill, highway construction, and the unbridled growth of the automobile) ensured that East Lake would be transformed in the second half of the twentieth century as substantially as it was with the coming of the streetcar in the late nineteenth century. Buoyed by the wartime Navy V-12 program and the G.I. Bill, Howard College needed more land on which to develop a campus for the post-war era. Its president, Harwell Davis, was loath to move out of Birmingham’s Jones Valley since many students commuted to Howard on the streetcar line. But in 1947 he was persuaded to purchase an undeveloped track of land in Shades Valley. This was just four miles from downtown Birmingham, but was over the steep Red Mountain and the smaller Bald Ridge, so it had not developed in the streetcar era of Birmingham.

After some delays, construction of the new Shades Valley campus for Howard College began in earnest in 1955. The following year the Supreme Court of the United States invalidated the premise of “separate but equal” education that had undergirded the American racial system for over sixty years. The court called for desegration with all “deliberate speed.” Liberals emphasized the noun, “speed.” Moderates emphasized the adjective “deliberate.” Conservatives resisted both.

The next year, Howard College moved to Shades Valley. Three years later, Eastwood Mall, the first enclosed shopping mall in the Deep South, opened just a little over two miles from East Lake, but “over the mountain” from the old urban community. East Lake’s days as a neighborhood of choice for Whites were over.

The increased traffic the mall created through Red Gap made the widening of the road into what is now known as Oporto-Madrid Boulevard a top priority. It was completed in 1962, the following year the success of the civil rights movement “Operation C” at the older center of commerce in downtown Birmingham speeded the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the desegregation of public schools, and White Southerners’ efforts to thwart it by moving to the suburbs. While in retrospect these factors spelled the future transformation of East Lake that was not immediately evident at the time. Several handsome churches in modern styles were built through the 1960s.

1970s and 1980s: Forging a New Birmingham

Readers might be familiar with the Christian sports film Woodlawn (2015) . Depicting the story of the football team at Woodlawn High School, a couple of miles west from East Lake in the early 1970s, it offers a helpful interpretation on the era. The rival team to Woodlawn in climatic moments of the film is Banks, the high school that served East Lake (L. Frazier Banks High School). This era is a key time of transition in the history of religion, ethnicity, and race in East Lake. By the 1980s, some White congregations were moving to new opportunities further to the north and west. While most congregations remained until after 1990, their life changed substantially.

In 1979, Richard Arrington, a graduate of and professor at Miles College became the first African American mayor of Birmingham. His election marked both the sucess of the Civil Rights Movement and the flight of Whites to the suburbs. The most attractive suburbs were over Red Mountain to the south, but many also moved out of Birmingham to northern communities such as Gardendale and Trussville. While few congregations moved out of East Lake before 1990, many younger Whites did. Their migration out of the neighborhood was followed by the churches in the subsequent decades.

1990s and 2000s Living into a New Reality

In 1970, there were approximately twenty White-founded churches within a one-mile radius of the original site of Ruhama Baptist Church. In 2024, there were just three: East Lake United Methodist Church, East Lake Highlands Church of God of Prophesy, and St Barnabas Roman Catholic Church. Two more were just over the line: Lakewood Baptist Church and Citizens Church, new church that worshiped in its same building.

Many congregations, including the storied Ruhama Baptist Church disbanded, even if they nominally affiliated with a nearby congregation of the same denomination. (At its closing, Ruhama’s legacy was to be sustained by Irondale Baptist Church, but that congregation later moved and took the name “Church at Grants Mill: An SBC Fellowship” while doing little if anything to sustain its 200-year-old heritage).

Several others moved to the northeast to found new congregations. East Lake Cumberland Presbyterian Church reestablished itself on Old Springfield Road in Pinson in 1988 as Advent Cumberland Presbtyerian Chruch. East Lake Alliance Church moved north east into unincoprated Jefferson County in 1991 becoming Brewster Road Alliance Church. Faith Lutheran Church moved from East Lake to Deerfoot Parkway in 1999. By 2014, the legacy of both Seventy-Sixth Street Presbyterian Church and East Lake First Presbyterian Church would be continued by Cahaba Springs Presbyterian Church.

[map showing moves]

The Twenty-First Century

While much has changed in East Lake since 1990, it is worth noting that approximately 15 of the 17 properties that Whites had developed as churches were still used as churches in 2000 (and most still in 2024). Once a spot in the landscape becomes a church, in a neighborhood like East Lake it is likely to remain a church.

Some new congregations have moved into the neighborhood. Citizens Church was founded in 2019 with the aspiration of being multi-racial. It meets in the building of Lakewood Baptst Church, a historically white congregation that has remained in the neighborhood.. East Lake United Methodist has for decades had a strongly neighborhood-focused ministry. Even among histoic churches there have been significant changes in the racial identity of the leadership: beginning in 2019, St. Barnabas Roman Catholic Church was led by a priest born in Asia.

Only 1 long-standing Black owned church property had been abandoned. This church moved east to Kingston. Four other long-standing (founded prior to 1970) churches remain, and many Black congregations have moved in or were founded in the neighborhood and remain.

If Hosea Holcombe and the other founders of the English-speaking settlement in East Lake could have looked 200 years into the future, it is difficult to know what they would have fathomed. Interstates and cellphones are both a daily part of East Lake life, yet thsy were surely beyond their ken. The United States’ free market for religious communities has remained a constant as has the importance of maintaining and contesting the racilal classification of its citizens. These themes, i expect, will be evident in Samford’s students’ studies of the community.

References

Bee, Fanna K., and Lee N. Allen. 1969. Sesquicentennial History, Ruhama Baptist Church: 1819-1969. Birmingham, AL: Ruhama Baptist Church.

Martin, Joel W. 1991. Sacred Revolt: The Muskogees’ Struggle for a New World. Boston: Beacon Press.