The Forgotten Founding Father

By Tanner Wages

George Whitefield, an English evangelist, was born December 16, 1714, in Gloucester, England. His birth town was close to one hundred miles west of London and was very plain. George was the youngest of seven children born to Elizabeth Edwards and Thomas Whitefield. He began his education with his mother, Elizabeth, and then attended St. Mary de Crypt School before starting at Pembroke College in Oxford.

Thomas S. Kidd, who serves as a research professor for Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, stated in his book, George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father, that Whitefield was “born in a time of profound political and religious transition for England.” One hundred eighty years before his birth, King Henry VIII had separated England from the Roman Catholic Church (Kidd 2014, 6). In the intervening centuries the identity of the Church of England was highly contested. Catholics, staunch Reformed Protestants, and modernate Protestants all had their day. Whitefield would later echo those who went before him when describing Catholicism as the most “destructive religion in the world; as not deeming any people worthy to live upon the earth, but the slaves of papal jurisdiction” (Kidd, 2014, 7). While Whitefield remained within the Church of England be came to center his preaching on the necessity of an experience of new birth after baptism.

The New Birth

George Whitefield was known for his emphasis on the new birth. In Whitefield: the Heart of an Evangelist, Jared Hood points out four key ideas to understand Whitefield’s identity. The first was the centrality of the new birth. Most theologians of his day focused on justification and covenant while Whitefield leaned into the idea that faith was a gift and the sinner must come to have a relationship with God (Hood 2010, 165-66). Whitefield echoed what Martin Luther had proclaimed when he nailed the 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, in 1517.

George Whitefield is often associated with John and Charles Wesley brothers since they also focused on the new birth. However, when discussing the differences between Whitefield and the Wesleys, Jared Hood states, “to put the difference into its broadest context, [John] Wesley was an Arminian who believed that election took place on the basis of God’s foresight of human faith (conditional election, or a foreknowledge not of His own will but of contingent events), whereas Whitefield was a Calvinist, who, with the Thirty Nine Articles, made no such qualification” (Hood 2010, 168).

The Great Awakening & Its Implications

Despite their differences on this point, Whitefield and Wesley both had their greatest affect on America as part of the series of movements remembered as the Great Awakening. He joined John and Charles Wesley in their missionary work in the colony of Georgia in 1738 because of his interests in the Great Awakening, a series of religious revivals in America. The Great Awakening was an encouragement to those who did not have high social status. Oneof its central themes was that anyone could have a relationship with God without relying on church leaders. Whitefield preached to numerous large audiences and his style would attract people from all over, thereby spreading the message of the gospel far and wide.

Most colonial clergy welcomed Whitefield and his new ideas; however, accounts in newspapers report that a decline in church attendance soon followed his success (Leyerzapf 2012, 4). Many questions arose as a result of Whitefield’s presence in the pulpit, including “What constitutes good preaching?” and “Who is fit to preach?” (Leyerzapf 2012, 4). Those congregants who welcomed Whitefield typically held more democratically-inclined views while those who did not approve of him desired to keep the status quo. The opposition to Whitefield and his teaching were “attacks on Whitefield’s character, attacks on his practices, and concerns about the effects of his message” (Leyerzapf 2012, 5).

Certain people had a hard time supporting Whitefield because he did not believe that church leaders enabled one to have a relationship with God; instead, he believed faith in God was the result of God’s grace and a personal decision. Whitefield clearly shows enthusiasm without solely using biblical texts to support his discussion. He was quick to defend himself after his first New England tour by issuing a response to the critical pamphlet “The State of Religion in New England, since the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield’s Arrival There” (Leyerzapf, 2012, 9). He was quick to defend himself and the actions that had been taken to bring him down, primarily in sermons and occasionally in print. While he believed these attacks on him were from the devil, he also believed that God, in his infinite mercy, had carried him and would continue to do so. The questions originally asked of George Whitefield are still questions asked today (Leyerzapf 2012, 18).

Whitefield & His Impact on America

Ultimately, George Whitefield changed how the world saw one’s ability to have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. However, Whitefield’s goal was to bring souls to Christ, not to invoke controversy. He preached a God-centered gospel. This is a message where the glory of God and depravity of man is fundamental. It is unlike a man-centered gospel which teaches that God’s priority for us is our happiness rather than our need for him. Whitefield was far from perfect, yet he aimed to live a life that glorified God. He needs to be remembered by our nation and by Samford because of the perseverance he showed in a hate-driven world. He defended what he believed in even if it was unpopular. Thomas Kidd states, “Whitefield was the key figure in the first generation of evangelical Christianity” of the three major evangelical figures of time, John Wesley, Jonathan Edwards, and George Whitefield, “he linked, by far, the most pastors and leaders through his relentless travels, preaching, publishing, and letter-writing networks” (Kidd, 2014, 260).

Without Whitefield, Anglo-American evangelicalism would have barely been represented throughout the world. He started evangelicals’ use of the media. He clearly used media and saw the gospel message as being “so critically important that he felt compelled to use all the earthly means to get the word out” and witness to those near and far (Kidd 2014, 260). Whitefield should also be remembered because, even with all the criticism aimed toward him in his life, slavery was not among the attacks. Finally, Whitefield was one of the first to begin the process of blending politics, war, and religion. Kidd recounts how the Reverend Samson Occom, a Presbyterian minister and member of the Mohegan nation, describes a vivid dream about his deceased friend, George Whitefield, and about Whitefield’s desire for those to preach the true Gospel of Christ.

Kidd concludes: “a man of his time, Whitefield had serious faults, which contemporaries pointed out and which are even easier to see from the vantage of three centuries. And yet he was a gospel minister of substantial integrity, spiritual sincerity, and phenomenal ability, and indefatigable energy” (Kidd, 2014, 263). May that be our purpose in remembering Whitefield and may that be an encouragement and a goal for every individual. Christ extends grace so that His followers may continue in the race until it is finished.

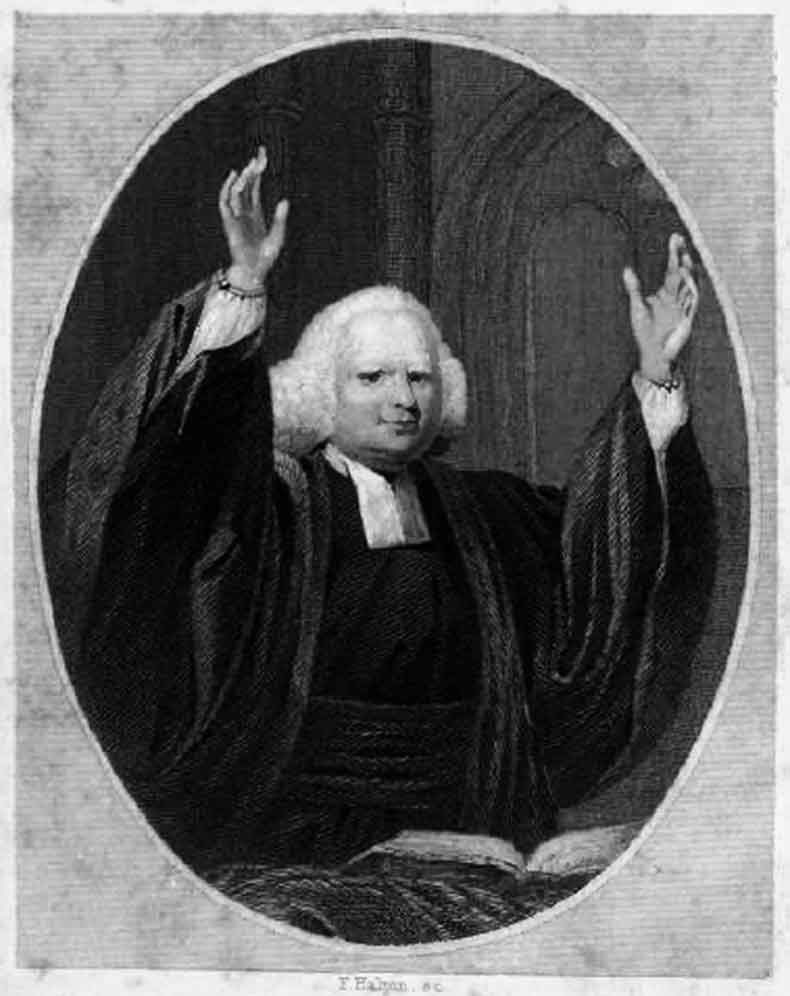

George Whitefield

Medium: Carved cherry wood

Artist: Artists of Létourneau Organ Company

Created and Installed: c. 2001

Location: Andrew Gerow Hodges Chapel, Samford University, 800 Lakeshore Drive, Birmingham Alabama, 35229

Bibliography

Blecher, Joseph. 1857. George Whitefield: A Biography. American Tract Society.

Hood, Jared C. 2010. “Whitefield: The Heart of an Evangelist.” Reformed Theological Review, The 69 (3): 164–79. http://www.doi.org/10.3316/informit.807796184105104.

Kidd, Thomas S. 2014. George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father. Yale University Press.

Leyerzapf, Amy. 2012. “George Whitefield and the Great Awakening: Implications of the Itinerancy Debate in Colonial America.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 42 (1): 44–64. doi:10.1080/02773945.2011.618172.

Tanner Wages ‘27 was a student in UCS 102: Memorials & the Future in Samford University’s Howard College of Arts & Sciences in spring 2024.

2 Comments