Warrior and Shepherd

By George Hall

In 2007, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth returned to Selma, Alabama, for a ceremonial crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where peaceful protesters were attacked by police on March 7, 1965, an event remembered as the “Bloody Sunday” march. On this day, Shuttlesworth met a young U.S. Senator from Illinois named Barack Obama. David Remnick recalls one of the most powerful images of the day in his book The Bridge. Shuttlesworth had recently had a brain tumor removed, so Obama pushed Shuttlesworth in his wheelchair across the bridge. This moment was powerful not just because within a year Obama would become the first African American president of the United States; it was powerful because it showed that Shuttleworth’s work would not be left behind in his death but would be brought into the next generation by Americans like Obama.

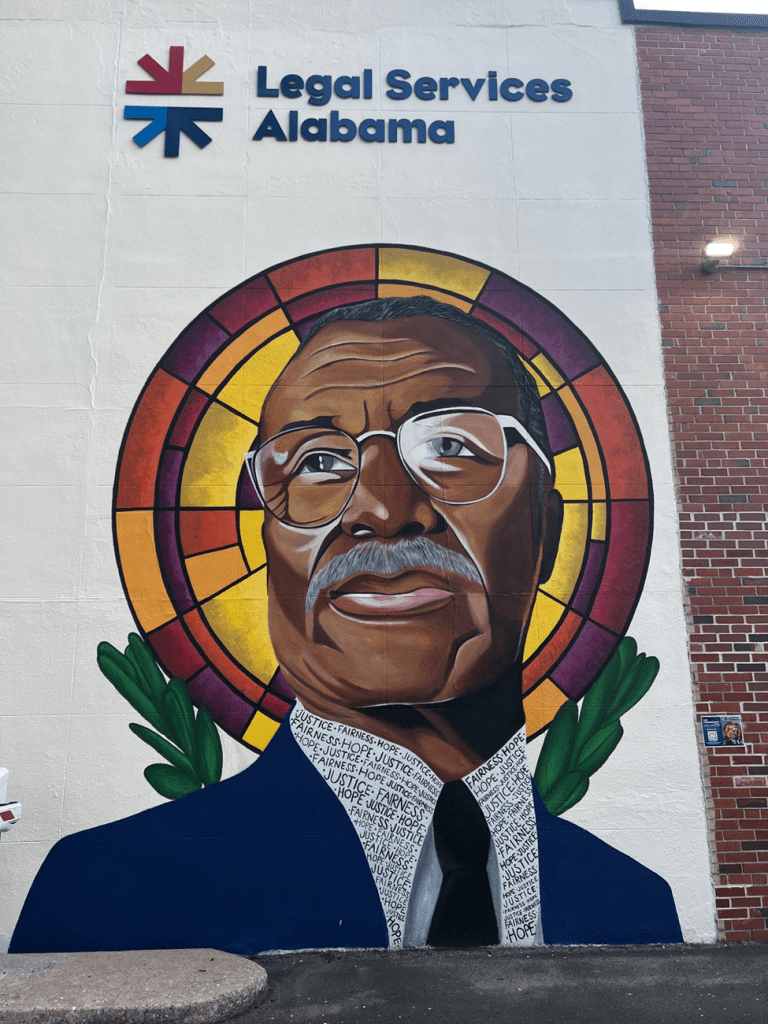

In commemoration of Shuttlesworth’s life and legacy, a mural of Shuttlesworth was painted by on the Legal Services Alabama building in downtown Birmingham on April 23, 2023. Like all good pieces of commemorative art, the painting has deep symbolism. It portrays Shuttlesworth as both a political activist, as well as a fiery preacher and man of God.

Shuttlesworth, the Activist

Shuttlesworth is best known for his contributions to the civil rights movement in Birmingham. When Shuttlesworth moved to Birmingham in 1953 to become pastor of Bethel Baptist Church, the movement had not really taken off yet, and it was looking for a launching point. There seemed to be no better place for that than Birmingham, the domain of Bull Connor himself, the king of segregation. Shuttlesworth himself later told Martin Luther King Jr. that “Birmingham is where it’s at, gentlemen . . . . If you win in Birmingham, as Birmingham goes, so goes the country” (Bass 2021, 98). From a young age, Shuttlesworth and those around him felt as though he was going to be different. Shuttleworth’s widow, Dr. Sephira Bailey Shuttlesworth recollected that “Shuttlesworth felt that he was being prepared for something greater and as a child he didn’t know what that meant. He said that other people saw it too though. He said that his teachers and folks at church oftentimes they’d say ‘Boy, I see something in you’” (King and Whitson 2022).

Shuttleworth’s ministry as a pastor was critical to the movement because in 1956, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was banned by the State of Alabama. However, the state was not allowed to outlaw religious organizations, so Shuttlesworth started the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) to continue the movement. Its protests started with mostly bus protests, especially after the Montgomery bus boycotts made a significant impact, but no action was taken in Birmingham after the ACMHR demanded that the Birmingham Transit Company “remov[e] signs separating the Races in Buses and Street Cars [and seat] all Passengers on a first Come-first Served basis” (Frohardt-Lane 2020, 290). Shuttlesworth was not merely an organizer of these protests, but he was leading his men into battle by sitting where he wanted on the bus. He paid a severe price for this. On Christmas Day 1956, Shuttleworth’s home was bombed while his kids were opening presents. Despite this, Shuttlesworth did not back down. He sat in the front of the bus the very next day.

Shuttlesworth continued his work in the city, but when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. decided to come to help, it took the movement to a whole new level of momentum. Shuttlesworth and King first met in 1954, and they quickly developed mutual respect and admiration for one another. Shuttlesworth recollected that they “didn’t talk for long…but I was impressed with his seeming humility and honesty…I was glad to meet someone who at last thought something could be done about segregation” (“News and Views” 2001). While King certainly held more influence nationally, King needed Shuttlesworth’s boldness throughout the movement. In spring 1963, when King was hesitant about letting the children march through Birmingham, Shuttlesworth stood tall and made sure it happened, and these protests were critical in applying pressure on the government to outlaw Jim Crow. At first these marches seemed to be going well, but Bull Connor, the commissioner of public safety, led police resistance to these marches with fire hoses and police dogs. Despite this adversity and future tragedies such as the infamous bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church, Shuttlesworth battled and battled to end racial injustice in Birmingham, and even though he did not see the results during his time there. while he was pastoring a church in Cincinnati, Ohio, he helped organize the march from Selma to Montgomery, which was one of the most critical moments of the civil rights movement. Shuttleworth’s efforts were critical to the civil rights movement, but his work as an activist was not Shuttleworth’s only contribution to the city of Birmingham.

Shuttlesworth the Preacher

Fred Shuttlesworth built his reputation around the city through his preaching, especially at Bethel Baptist Church in Collegeville. Historically, Bethel had stuck with older pastors, but in 1953 they were so “impressed with Fred’s charisma and strength of conviction” that they elected Shuttlesworth as the youngest pastor in the church’s history (Manis 1999, 71). This not only brought a sense of youth and vibrance to the life of the church, but it also gave the older members confidence in the direction of the church. Shuttlesworth was an extremely evangelistic figure, which in a way propelled him into his civil rights work. Shuttlesworth himself said “I do evangelism every time I talk to somebody . . . . If I’m talking to a person about a problem, I’m evangelistic in that” (Manis 1999, 71). This approach was critical in the formation of Fred Shuttlesworth the activist; Shuttlesworth never backed down. He wanted everyone on his team, and if you were not, he was going to try to win you over.

Shuttlesworth was a man of God, and after his house was bombed in 1956, he cited Psalm 27, especially the line that “The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear?” Even in moments of civil unrest and facing deep systemic oppression, Shuttlesworth still called upon the Lord. In an interview in 2007, Shuttlesworth explained where he got his boldness and tenacity for civil rights from: “I’ve always believed completely and totally that God would take care of me” (King and Whitson 2022). This was evident when Shuttlesworth took his daughters and another local boy to Philips High School after the Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision but was stopped by police and severely beaten and was taken to the hospital. The doctors told Shuttlesworth that he miraculously had not even suffered a concussion. Shuttlesworth attributed all of this to God, and then he went right back to work.

These moments in Shuttleworth’s life echo Psalm 121:1:“I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help” (KJV). Shuttlesworth also believed that his work for civil rights was the Lord’s will, no matter what others told him. Rev. Luke Beard, the pastor at 16th Street Baptist Church in 1956, tried to get Shuttlesworth to call off an ACMHR meeting by claiming that God told him to tell Shuttlesworth, but Shuttlesworth chirped back, “If the Lord wants me to call it off, He’ll have to come down from heaven Himself and tell me” (King and Whitson 2022). Throughout his ministry, Shuttlesworth used his faith to power his activism.

Remembering Shuttlesworth

The mural of Shuttlesworth in downtown Birmingham perfectly reflects this. First, the mural was painted on the Legal Services of Alabama building in Birmingham, painting Shuttlesworth as a political and social hero. His shirt collar is inscribed with the words “fairness,” “hope,” and “justice.” These were all mantras of the civil rights movement and are ideals our current government seeks to maintain, showing that the government of Alabama is trying to honor Shuttlesworth with their decisions. But Shuttlesworth is not only decorated politically, but he is also decorated as a religious hero. This is seen by the fact that Shuttlesworth has a halo around his head. This is a common ways to honor martyrs and saints in church iconography. While Shuttlesworth did not die for the gospel or even for the civil rights movement, he certainly suffered much from it, making him worthy of being a saint of the civil rights movement. Lastly, the laurels supporting the halo suggest that Shuttlesworth was victorious, which he was after all. It was a lengthy process, but Shuttlesworth saw the Voting Rights Act passed, the abolition of Jim Crow, and even the election of the first African American president in 2008.

Fred Shuttlesworth

Medium: painting on masonry

Artist: Meghan McCollum and Jamie Bonfiglio

Created and Installed: April 23, 2023

Location: Legal Services Building, 1820 7th Ave N Birmingham, AL 35203

Bibliography

Albert, Melissa. July 22, 2010. “Fred Shuttlesworth.” Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Fred-Shuttlesworth

Bass, S. Jonathan. 2021. Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders, And the “Letter From Birmingham Jail.” Updated edition. Baton Rogue: Louisiana State University Press.

Byington, Pat. 2023. “See New Powerful Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth Mural in Downtown Birmingham [Photos].” Bham Now. April 25. https://bhamnow.com/2023/04/25/see-new-powerful-rev-fred-shuttlesworth-mural-in-downtown-birmingham-photos/.

Eskew, Glenn T. 2000. But For Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Frohardt-Lane, Sarah. 2020. “Desegregating Birmingham’s Buses: African Americans’ Protracted Struggle and White ‘Civil’ Resistance.” Journal of Southern History 86 (2): 283. https://research-ebsco-com.samford.edu/linkprocessor/plink?id=6d31e9d7-c487-3ee3-8f5a-3d083fe3dd04.

King, T. Marie, and J. Whitson, producers. 2022. Shuttlesworth. Birmingham, AL: Alabama Public Television Documentaries, 2022. https://aptv.org/shuttlesworth/

Manis, Andrew M. 1999. A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

“News and Views: Fred Shuttlesworth: He Pushed Martin Luther King Jr. into Greatness.” 2001. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 33 (Autumn): 61-64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2678916.

Sorkin, Amy Davidson. 2011. “Postscript: Fred Shuttlesworth.” The New Yorker, 5 Oct. 2011, https://www.newyorker.com/news/amy-davidson/postscript-fred-shuttlesworth.

White, Marjorie L. and Andrew M. Manis, eds. 2000. Birmingham Revolutionaries: The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Edited by Andrew M. Manis. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

George Hall ’27 was a student in Core Seminar: Icons & Memorials in Samford University’s Howard College of Arts & Sciences in fall 2023.

Published November 28, 2023.

2 Comments